article> Opinion/Politics

The Problem with KU Leuven's Market Model

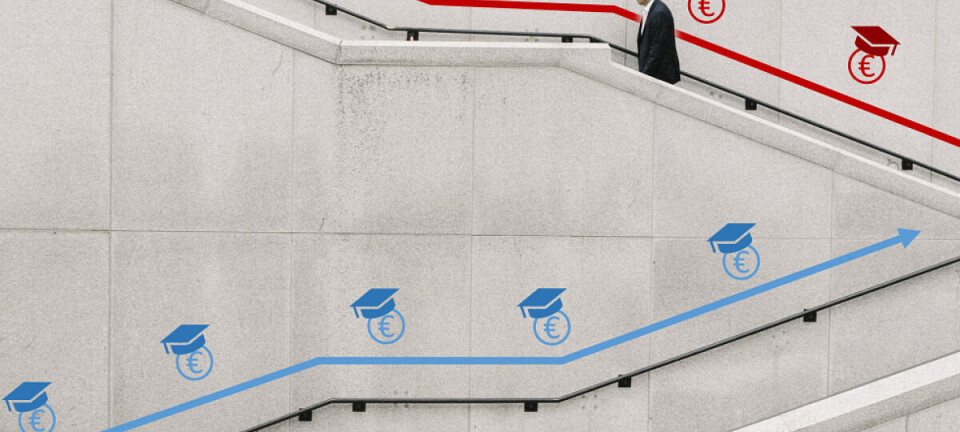

The increase in tuition fees for certain programmes at KU Leuven is seemingly a reflection of its market model view on education.

by Marit Pepplinkhuizen

Opinion/Politics Editor

KU Leuven: most innovative university in Europe

In October, it was announced that Reuters has named KU Leuven the 7th most innovative university worldwide. KU Leuven is the highest ranked institution outside of the United States. Of course, having our university ranking so highly would seem to be a good reason to rejoice. Who does not want to go to the highest-ranking university in Europe? Yet, what exactly does 'innovative' mean here?

Commercializing, patenting, marketing; these are not exactly words that are generally associated with an academic institution.

It turns out that in this context, according to Reuters, “innovative” means “the interest in protecting and commercializing discoveries”. Reuters based this interest on the amount of citations of academic papers and patent filings. Reuters praised the institutions in the top ten for their support to academics to publish, patent and market innovations.

In my opinion, we can clearly see the tendency of KU Leuven to act as a company in its recent policies like, for example, the increase of the tuition fees. The arguments used by the deans of the faculties all come down to the comparison with universities in Asia and the US. As dean Gerd van Riel of the Institute of Philosophy said in an article published by Veto in March 2018: “In comparison with British, American or even Dutch universities, in which you also have to pay more for extra support, we are still very comfortable here in Leuven. In the international context it is very cheap to study at KU Leuven. So much so that we have had reactions in the past from foreign students that there must be something wrong with the quality of the university if it asks such a low price.” To my mind, this does not seem to be a relevant argument for increasing tuition fees. The logic the dean uses here is only possible within the framework of a market model. We only need to take a look at the past to see that this market model is not a new development, and that the increase of the tuition fees is not a new policy that stands on its own.

A market model is bad for the EU as a whole

The brain circulation at which the Bologna declaration was aiming is not happening.

In 2009, 29 European ministers signed the declaration of Bologna. Its main aim was the creation of a European space for higher education. The declaration of Bologna wanted to increase mobility within Europe by measures such as introducing the Bachelor-Master structure, by introducing ECTS credits, and by implementing an exchange-system such as the well-known and popular Erasmus exchange. However, this rather utopian vision turned into a snake biting its own tail. Europe is now not only competing with the US and with Asia, but primarily with itself. Western-Europe is a very popular destination for exchange, whereas Eastern-Europe has much less exchange students to welcome. Thus, the exchange of skilled students leaves these sending countries significantly worse off. The brain circulation at which the Bologna declaration was aiming is not happening. What is more, it only leads to polarization between Eastern and Western Europe. Which brings us to the discrimination aspect of the increase of tuition fees.

Increasing tuition fees means increased polarization

Tuition fees at KU Leuven have only been raised for the students outside the European Economic Area (EEA). Until 2014, students of all nationalities paid the same amount of tuition fees. In that year, there was an increase of the tuition fees for students who do not belong to the EEA, which was introduced by several faculties: the programmes got the opportunity to raise the fees to 1750, 3500 or 6000 euros. Students not belonging to the EEA now pay 3500 euros in tuition fees for a bachelor’s or master’s degree in Philosophy, 1750 euros for a master’s in Economics and 6000 euros for a master’s in Bioinformatics. However, there is still a lot of uncertainty. Veto recently published an article in which it became clear that there is a special taskforce now to look at the option of homogenizing the tuition fees. There is talk of making it 4000 euros for every bachelor’s and master’s degree.

STURA held a survey to assess what the students of KU Leuven think about the increase of the tuition fees. Of the 165 respondents of the survey 146 thought that the increase of tuition fees is not reconcilable with a higher or similar degree of diversity. 140 respondents think that increased tuition fees will not increase the chance of attracting better students, and 148 respondents think that there will not be as many students who will enroll at KU Leuven.

Refugee students

Increases in the cost of education affects the most vulnerable in society the hardest. For example, Ali is a Somalian student studying anthropology at KU Leuven and he could not afford the 'normal' tuition fees. Therefore, he was obliged to apply for a scholarship. When interviewed he said: “I now have an 80% scholarship from the Social Services of the university. I came to Leuven in 2015 and first stayed in a camp for refugees. When I got my papers I moved to Leuven to search for schooling. However, I spent everything for my trip, I had to pay 12.000 euros to come here. I had to flee my country because it is not safe there right now. We didn't come here to study, we came here to live.”

“I cannot even pay 500 euros, so definitely not those high tuition fees.”

While talking to Ali, it becomes clear that the university does not have a transparent policy regarding refugee students, which is reminiscent of the vague policy around the tuition fees. KU Leuven advertises itself as welcoming towards refugees. Yet, as Ali has experienced, the process of actually getting into the university is very hard, and it is a lot less strict at other universities, as he found out from friends at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). “A lot of my friends are at VUB, since their process is easier. I think here at KU Leuven it is so hard because of the ranking and the name. They want to keep their name. In Ghent they actually even have free PhDs for refugees, they have a programme where refugees are welcome. Those things are not possible in Leuven.” As Ali emphasizes, when the system is this strict, the expenses involved with studying at KU Leuven can cause a lot of stress. “I want to do my fieldwork in Leuven, since for fieldwork you also have to pay rent and transportation. Students normally go to the Netherlands, for example. I will have to find it in Leuven because I don't have the money to travel. Also, I cannot be outside of Leuven more than 30 days because of my travel documents, and the fieldwork is at least 2 months. The government pays a minimum income for refugees, it is the lowest income for a human being. It is less than 1000 euros per month. So it’s impossible for refugee students to pay those high tuition fees”.

Consequences of KU Leuven's market model

It is not hard to see what other additional effects there may be from having a market model for a university. To name a few: companies can become too influential which could lead to biased research (as of now multinationals already hold 80% of the chairs in Leuven); the humanities and small majors are in danger of disappearing altogether; it will only be possible for 'rich' people to study, which means the university is in danger of becoming elitist and uniform.